Burial customs and funerary rites – Treasures of the Bronze Age cemetery of Nagycenk 4.

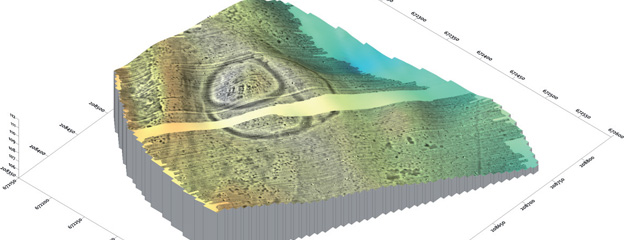

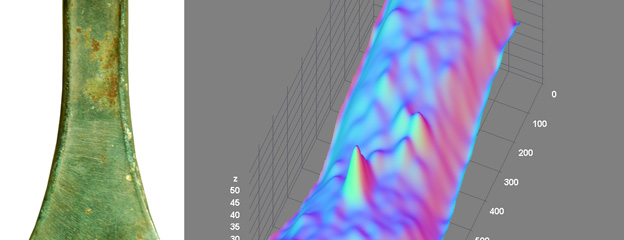

In our previous post, we attempted to reconstruct wooden remains, e.g. the use of a bronze axe from an elite burial (grave 55) discovered in the cemetery of Nagycenk-Lapos-rét, used between 2100 and 1750. On the basis of the organic residue found in the chieftain’s grave of the presumably elder generation of the cemetery (Grave 1), the remains of a young man (23-28 years old), accompanied by two daggers and a neckring, were covered with wooden planks (Gömöri et al. 2018, Fig. 3). Traces of log coffins with handles, as well as funerary beds are known from Zsennye and Austrian cemeteries of the Gáta-Wieselburg culture (Krenn-Leeb 2011; Nagy 2013). In most cases, the remains of those of higher social status were “protected” by wooden or stone structures in the afterlife.

Left: Grave 1 with wooden plank remains covering the skeleton (excavation photo by János Gömöri); right: the grave of an elite man aged between 30 and 40 years, reconstructed from the remains found in Grave 275, Hainburg, Austria (after Krenn-Leeb 2011, Abb. 24)

The orientation of the graves relative to the cardinals can refer to layers of the community’s worldview and faith that are difficult to recover. Like at other Gáta-Wieselburg cemeteries, the dead at Nagycenk were laid with their head pointing to the west/southwest. The burial of a 23-34 year old woman (Zoffmann 2008, 16) was an exception to the rule, oriented to the east and placed in a prone position (Grave 73). The uncommon orientation of the body may reflect the differing community perceptions due to the unusual circumstances of her death. Prone position is often considered to be associated with the periphery of society by archeological research. However, it is contradicted by the fact that several individuals with elaborate grave goods and even the ‘chieftain’ of Grave 55 were buried face down at Nagycenk.

Rituals and relatives

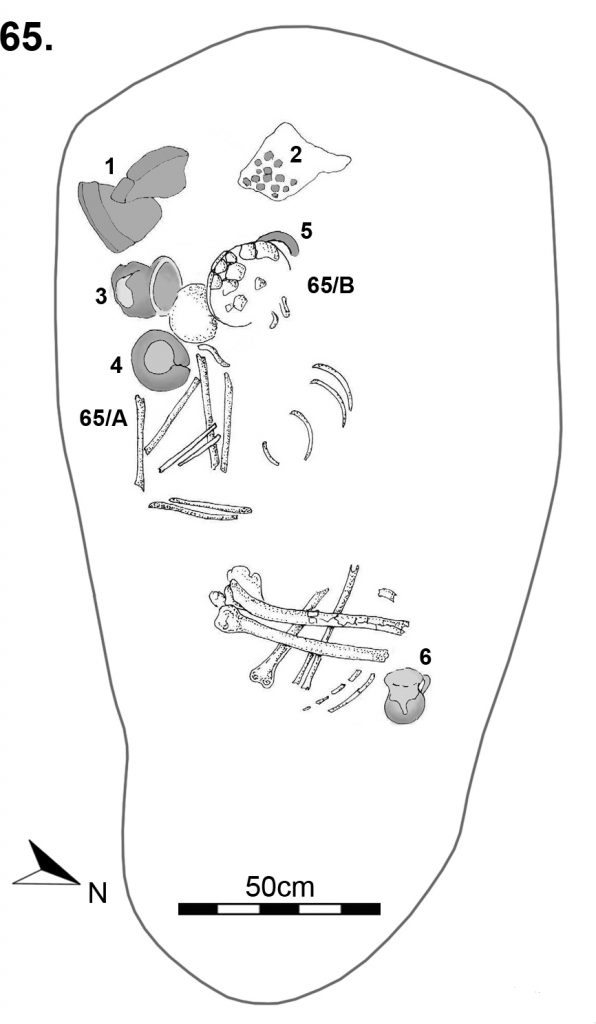

Nagycenk, Grave 65: double burial of a man and a woman (after Gömöri et al. 2018 Fig. 16.)

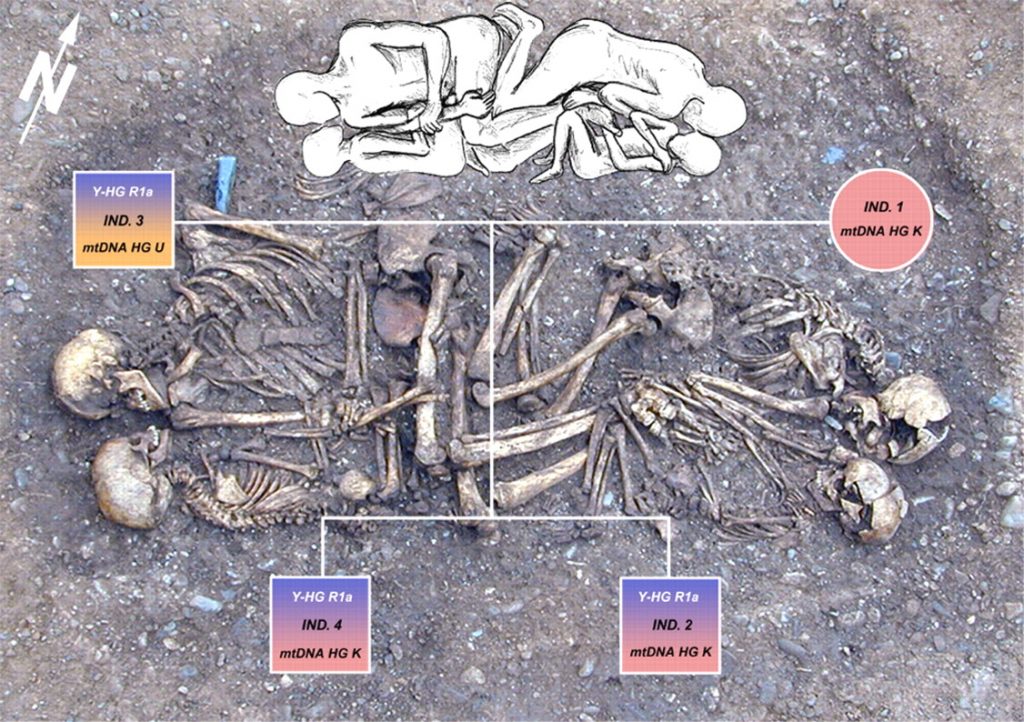

In most cases, individuals from close social or family relationships (e.g. mother and child, spouses, brothers and sisters) were buried in a common grave, which was confirmed several times by DNA analyses of contemporaneous burials in Germany (Haak et al. 2008; Knipper et al. 2015). The first results DNA testing carried out by our research group also revealed relatives between the deceased buried in Middle Bronze Age settlement pits (Kiss et al. 2018).

The family grave of Eulau (Grave 99) with results of genetic testing that revealed both maternal and paternal relatives (Haak et al. 2008, Fig. 2)

Traces of funeral feasting?

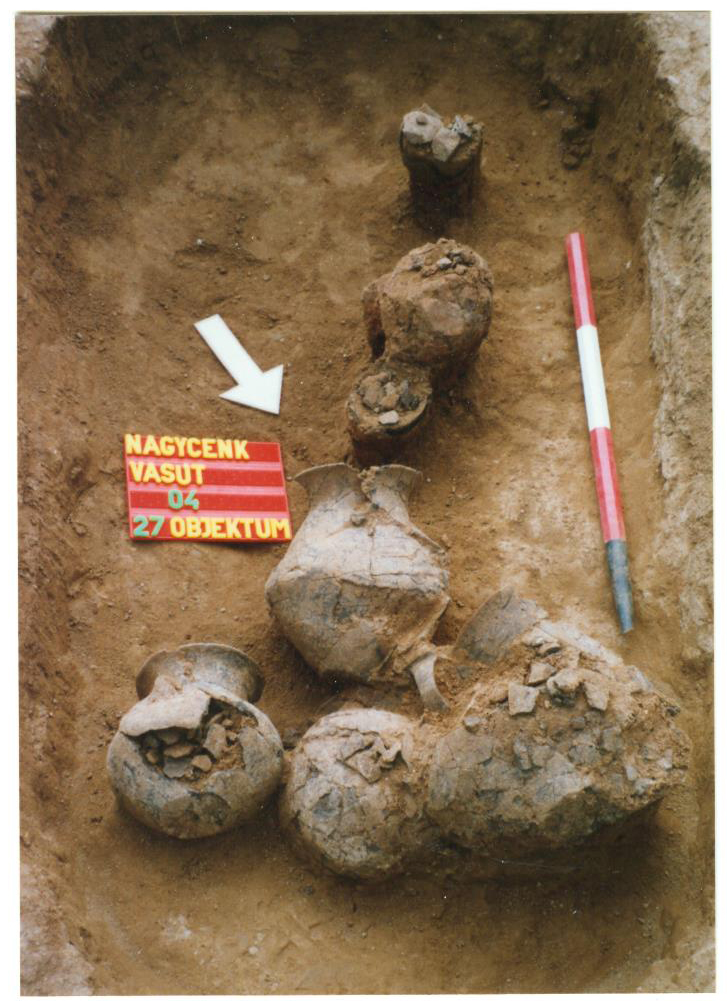

Nine vessels of varying sizes were placed in pit Nr. 27, situated at the edge of the Nagycenk cemetery. The pit was oriented like the graves, but it contained no human remains at all.

The excavation photo of the pottery deposit in pit Nr. 27 at Nagycenk (Photo: János Gömöri)

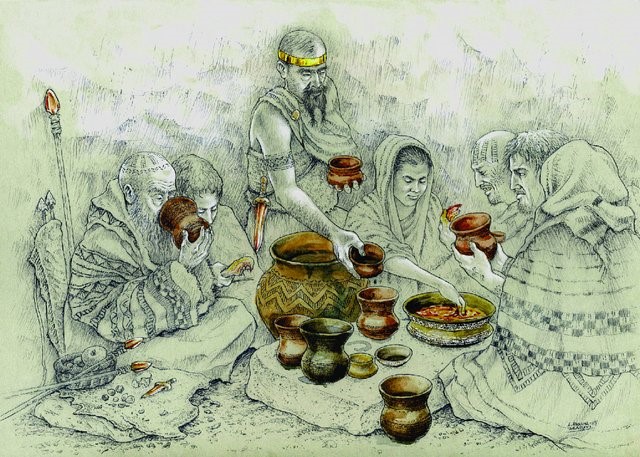

Bronze Age pottery finds within cemeteries, but out of graves may have been associated with rituals (e.g. feasting; Guerra Doce 2006; Rojo Guerra et al. 2008) performed at the burial ground to commemorate or bury the dead. At Zsennye, a similar pit containing ten vessels was situated next to the central grave of the oldest man in the cemetery (Nagy 2013, 116–117, Taf. 16). Both the Nagycenk and the Zsennye pottery deposits contained an almost equal number of storage and serving vessels in which food and drinks could have been prepared and brought to the venue of the ritual. The destruction of the utensils – that is, their deposition – may mean that after the objects had been part of a ritual act (e.g. a feast held at the funeral of a community leader), they could no longer be part of the everyday life and were thus disposed of use as “sacred waste” (Kalla et al. 2013, 28).

Reconstruction of a funeral feast based on contemporaneous (2500-2000 BC) finds from Spain (after Garrido-Pena 2007, Fig. 9)

Viktória Kiss – Eszter Melis

References

Gömöri J., Melis E., Kiss V.: A cemetery of the Gáta–Wieselburg Culture at Nagycenk (Western Hungary). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 69 (2018) 5–82.

Garrido-Pena, R.: El fenómeno campaniforme: un siglo de debates sobre un enigma sin resolver – The bell beaker phenomenon: a century of debate on an unsolved enigma. In: Cacho, C., Maicas, R., Martínez, M.I., Martos, J.A. (eds): Acercándonos al pasado: Prehistoria en 4 actos. Madrid. Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Ministerio de Cultura 2007, 1–16.

Guerra Doce, E.: Exploring the significance of beaker pottery through residue analyses. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 25 (2006) 247–259

Haak, W., Brandt, G., de Jong, H. N., Meyer, C., Ganslmeier, R., Heyd, V., Hawkesworth, C., osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 105, 18266–18231.

Kalla G, Raczky P., V. Szabó G.: Ünnep és lakoma a régészetben és az írásos forrásokban. Az őskori Európa és Mezopotámia példái alapján. In: Convivium – Az Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem Bölcsészettudományi Karán 2012. november 6–7-én tartott vallástudományi konferencia előadásai & Gaál Balázs Vegetarianizmus és nem-ártás az ókori Indiában–Keleti és nyugati perspektívák. Ed.: B. Déri. ΑΓΙΟΝ könyvek 2. Budapest 2013, 11–46.

Kiss, V., Barkóczy, P., Czene, A., Dani, J., Endrődi, A., Fábián, Sz., Gerber, D., Giblin, J., Hajdu, T., Káli Gy., Kasztovszky, Zs., Köhler, K., Maróti, B., Melis, E., Mende, B. G., Patay, R., Pernicka, E., Szabó, G., Szeverényi, V., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Reich, D., Kulcsár, G.: People and interactions vs. genes, isotopes and metal finds from the first thousand years of the Bronze Age in Hungary (2500-1500 BCE). In: Genes, isotopes and artefacts – How should we interpret the movements of people throughout Bronze Age Europe? Multidisciplinary conference, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, 13-14. December 2018. Abstract book, p. 6.

Knipper, C., Fragata, M., Nicklisch, N., Siebert, A., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Hubensack, V., Metzner-Nebelsick, C., Meller, H., Kurt, W.A. (2015): A Distinct Section of the Early Bronze Age Society? Stable Isotope Investigations of Burials in Settlement Pits and Multiple Inhumations of the Únětice Culture in Central Germany. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 159/3, 496–516.

Krenn –Leeb, A.: Zwischen Buckliger Welt und Kleinen Karpaten – Die Lebenswelt der Wieselburg-Kultur. ArchÖ 22 (2011) 11–26.

Nagy, M.: Der südlichste Fundort der Gáta-Wieselburg-Kultur in Zsennye-Kavicsbánya/Schottergrube, Komitat Vas, Westungarn. Savaria 36 (2013) 75–173.

Rojo Guerra, A.M, Garrido-Pena, R., García-Martínez-de-Lagrán, I: Everyday routines or special ritual events? Bell Beakers in domestic contexts of inner Iberi. In: Baioni, M., et al. (eds): Bell beaker in everyday life. Proceedings of the 10th Meeting “Archéologie et Gobelets”, Florence–Siena–Villanuova sul Clisi, May 12-15, 2006. Firenze 2008, 321-326.

Zoffmann Zs.: A bronzkori Gáta-Wieselburg kultúra Nagycenk-Laposi rét lelőhelyen feltárt temetkezéseinek embertani vizsgálata (The anthropologic study of the burials unearthed at the Nagycenk-Laposi rét site of the Bronze Age Gáta-Wieselburg culture). Arrabona 46 (2008) 9–34.