Traces of social stratification: the treasures of the Bronze Age cemetery at Nagycenk 2.

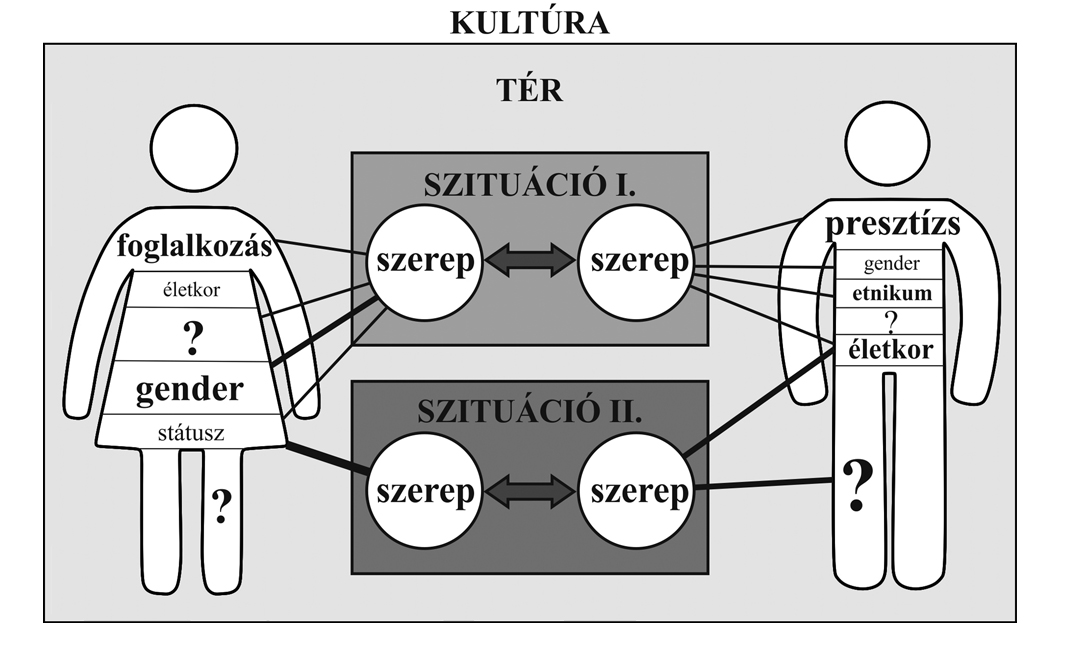

In our previous article on the findings of the cemetery at Nagycenk, we have mentioned that burials can testify several phenomena. Among many other things, they can reflect the identity of the deceased defined by the social (individual and group, kinship, gender) roles they fulfilled during their lives and the commemoration of the mourning community as well (Koncz-Szilágyi 2017). In the followings we focus on the portrait depicted by the grave goods possibly referring to social status.

Potential identities of an individual (After Koncz–Szilágy 2017, Fig. 2.)

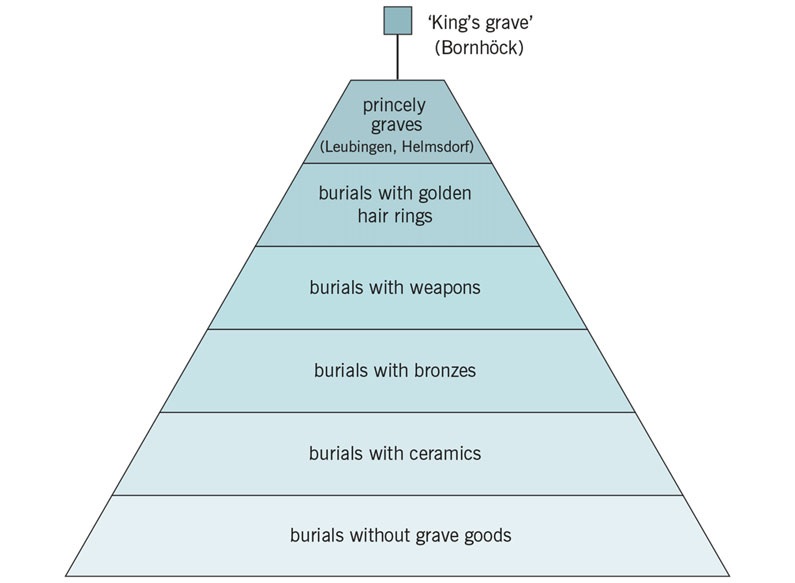

Chiefs at the top of the social pyramid

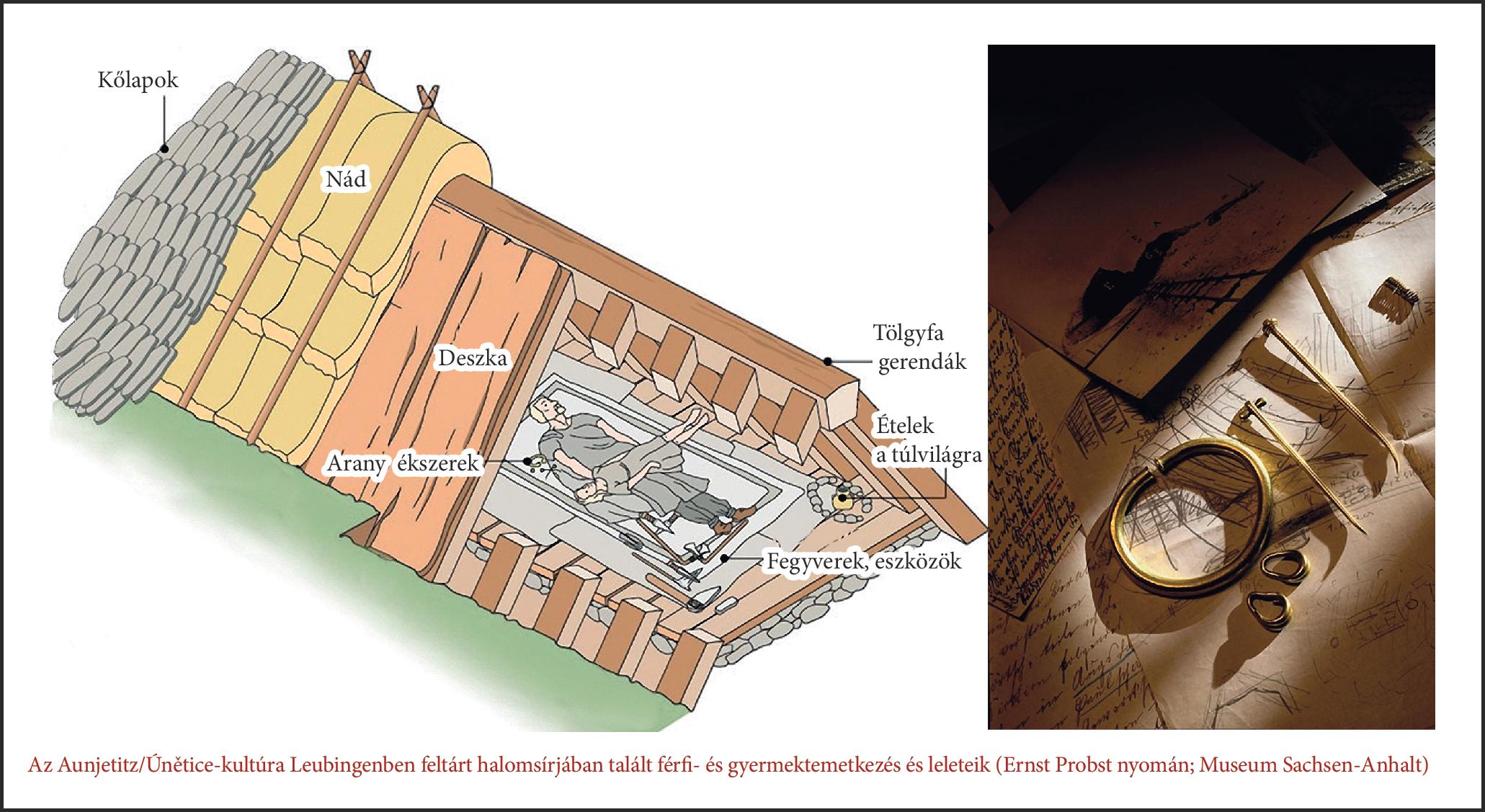

In recent years, several attempts have been made to reconstruct the social structure of European Bronze Age communities. Similarly to the cemetery at Nagycenk, the evaluation of the find material of the Gáta-Wieselburg culture cemetery at Zsennye and the burials of the Aunjetitz/Únětice culture in Central Germany served as the basis for the analysis. The graves of this latter culture in Germany suggest that noble leaders were positioned at the top of the social pyramid, such as those buried into the princely tumuli of Leubingen and Helmsdorf, dating between 1940 and 1810 BC. Their high status was indicated by their golden attachments: hair rings, arm rings and pins used for fixing garments, as well as the multiple pieces of copper or bronze daggers, halberds and axes placed in the grave.

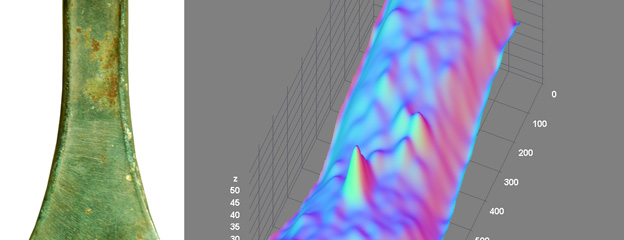

Bronze axe and golden hair rings from Osmünde, East Germany

(Schwarz 2014, Abb. 6)

The grave chamber and findings discovered in Leubingen

(Credit: Határtalan Régészet; after Ernst Probst, Museum Sachsen-Anhalt)

Perhaps the existence of some people who had even higher status than these “princes” is reflected by the large number of golden artefacts found at Bornhöck near Dieskau. The hoard consisting of a neck ring, three arm rings and an axe was associated with a tumulus grave that was originally 20 m high and 65 m in diameter. The top-ranking chiefs in the hierarchy were followed by those who were buried with fewer golden attachments (mainly with hair rings). Group 3 corresponds to warrior graves, while Group 4 includes individuals who have been buried with smaller bronze jewelry. The last two groups (5-6) indicate deceased accompanied by ceramic finds only, and burials without (preserved) grave goods (Schwarz 2014; Meller 2017).

Social hierarchy model of the Aunjetitz culture (Meller 2017, Fig. 2)

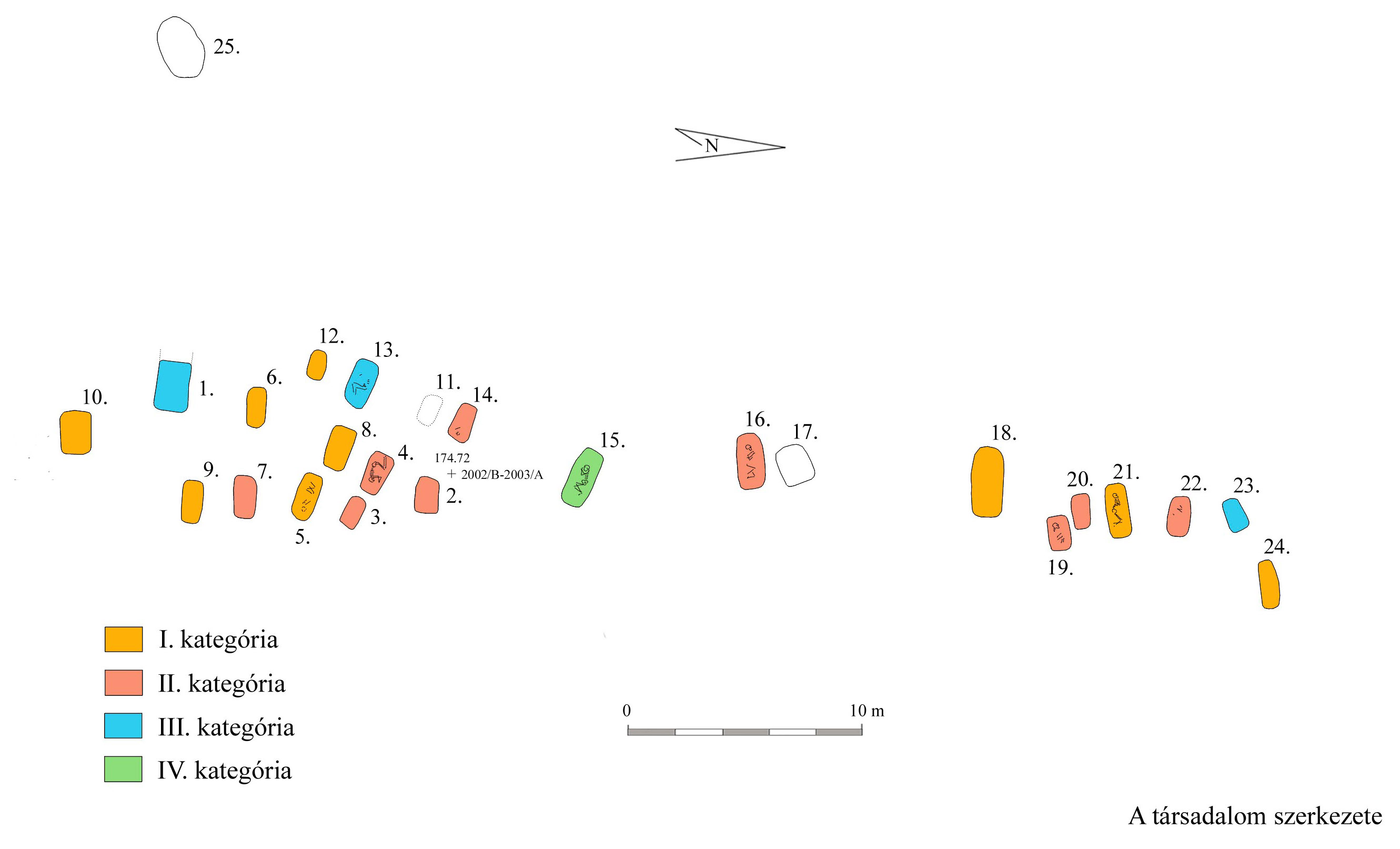

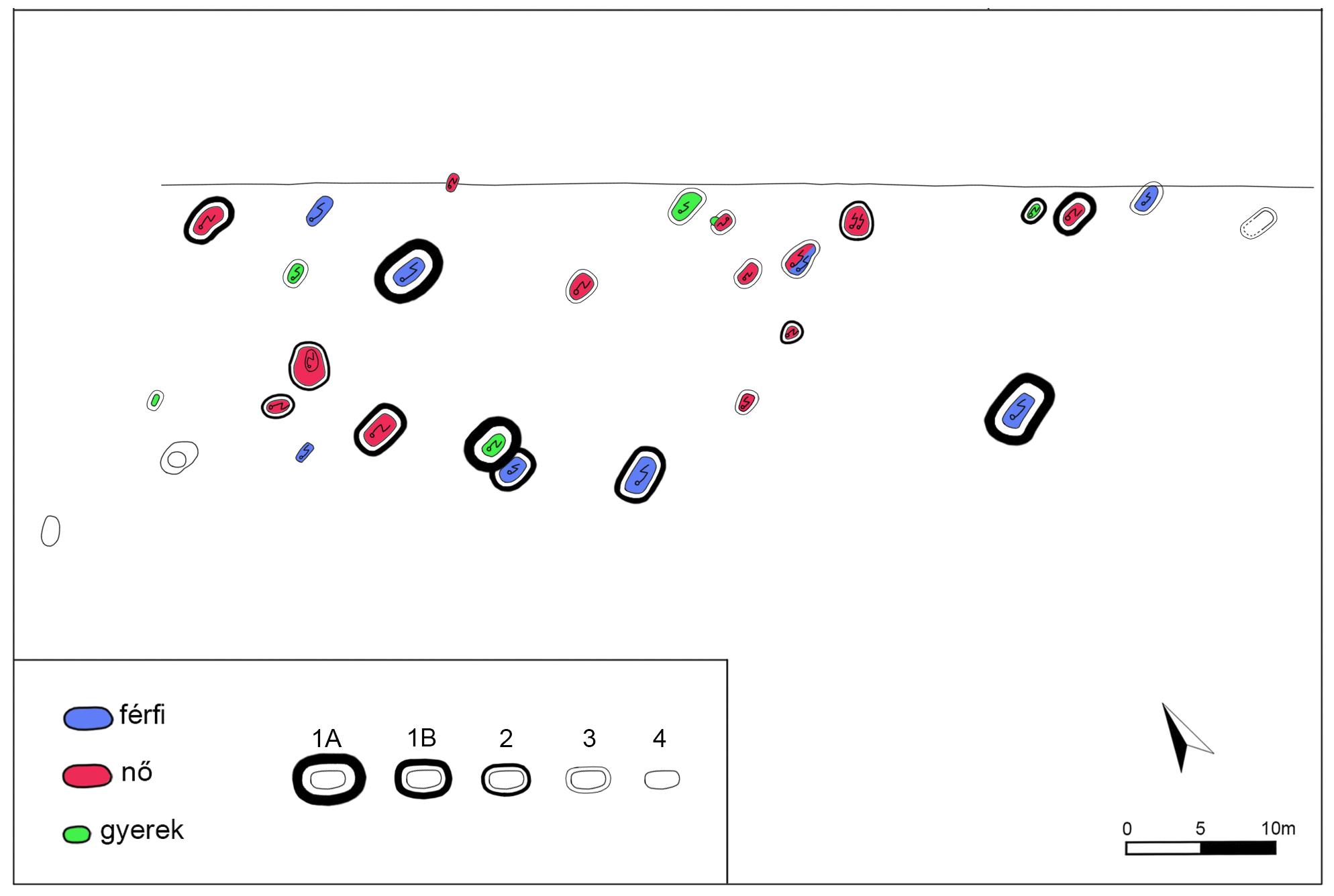

Social stratification in the Bronze Age of Western Transdanubia

In the recently published analysis of the 23 graves of the Gáta-Wieselburg culture cemetery at Zsennye, Marcella Nagy classified the deceased in different social categories, similarly to the German examples (in her system, category IV refers to the highest rank, while category I includes burials without grave goods). The only high status man (probably the local leader) in the cemetery of Zsennye could be the one who was equipped with two neck rings and a pair of golden hair rings. The number of graves with bronze grave goods is relatively low in this cemetery, only three more graves can be classified as burials of people with higher status. At the same time, the proportion of graves including only ceramic finds or nothing at all is relatively high (Nagy 2013, 116-117, Taf. 40).

Social categories in the cemetery of Zsennye (http://sirasok.blog.hu/2010/01/19/a_fiuk_a_banyaban_dolgoznak_5)

Based on the examples described above and on the analysis of the grave goods from the Nagycenk cemetery, we set up five social categories. The richest graves were divided into two subcategories by the number and raw material of the attachments, especially by the lack or presence of golden hair rings. Thus, each category can be compared to the bottom five levels of the social hierarchy model of the Aunjetitz culture.

Bronze axe and golden hair rings from Grave 55 (Photo: Hámori Péter)

Category 1a includes the two men who have been buried with golden hair rings and bronze axes: the middle-aged warrior in Grave 55, who was certainly one of the leaders of the village, and the child in Grave 53, equipped with golden and bronze jewelry. The young man buried in a wooden structure in Grave 1, who was accompanied by two copper neck rings, two daggers, an armring and a pin was also classified into this group. Category 1b may include men and women with a slightly lower status, equipped with copper or bronze daggers, jewels (neck rings, diadems, pins), but buried without golden artefacts. Category 2 refers to women and children buried with tiny bronze jewels. Bronze and golden artefacts placed in the children’s grave suggest the inheritance of material goods associated to social rank within the Bronze Age community. Category 3 includes ten individuals whose graves were furnished with only ceramic finds. The four persons (three adults and a child) buried without any attachments belong to Category 4.

Map of the Bronze Age cemetery part at Nagycenk-Laposrét, indicating the social status of the deceased by category numbers

(Map by László Gucsi, based on the map of János Gömöri)

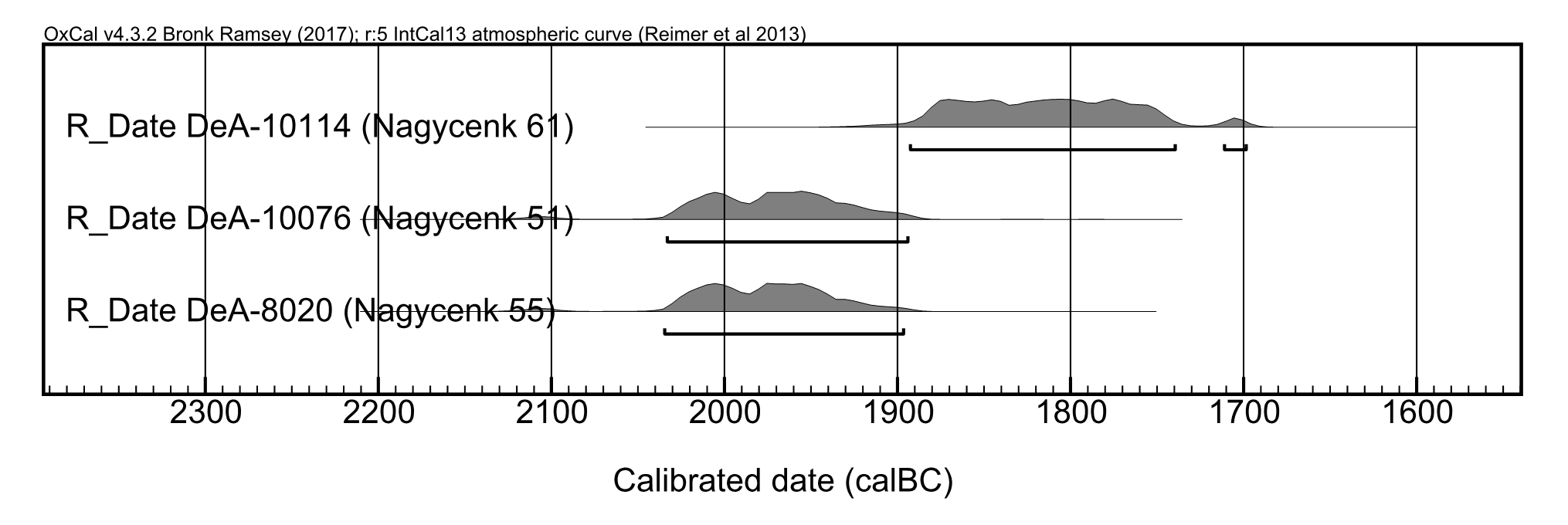

The proportion of higher status graves is much larger in Nagycenk than in the heavily disturbed cemetery of Zsennye. Based on the three radiocarbon data available from Nagycenk, the earlier burials were established between 2020 and 1940 BC and the use of the cemetery may have ended between 1880 and 1770 BC. On this basis, the two oval grave groups could serve as eternal resting place for individuals belonging to the households of some generations of community leaders.

Radiocarbon dates available from Grave 51, 55 and 61 at Nagycenk-Laposmező (After Gömöri et al. 2018, Fig. 41)

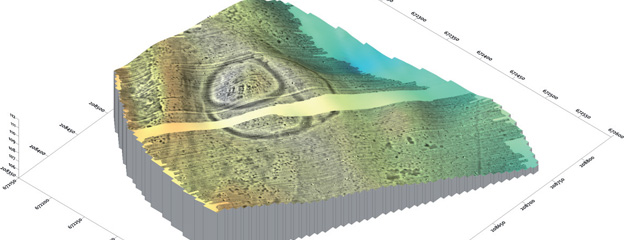

After the analysis of the findings revealed by former excavations we plan systematic field survey and geophysical measurements between the Arany Creek and Lake Fertő. Our aim is to get the fullest picture of the entire territory of the Bronze Age cemetery and settlement at Nagycenk, if possible. Further burials of the era have been discovered a few weeks ago during the preliminary excavations of Route 85, by the Rómer Flóris Museum of Art and History, coordinated by the Budavári NKft.

In the following articles, we will discuss the organic material residues and funeral customs of the Early and Middle Bronze Age burials, and later, the Bronze Age settlements around Nagycenk.

Viktória Kiss – Eszter Melis