Bronze Age Embodied 1.2. How can we imagine the chief from Balatonakali?

As it turned out from our previous post, the chiefly burial at Balatonakali was not discovered by an archaeologist. In this way no drawing or photograph was made of the exact location of the skeleton and the objects placed next to it. In order to present the man and his burial, we made a possible reconstruction of the grave based on the information available from similar finds, and we also tried to provide a picture of the clothes of the elderly man “embodied” from the skeleton.

Reconstruction of the chiefs’ burial and his objects

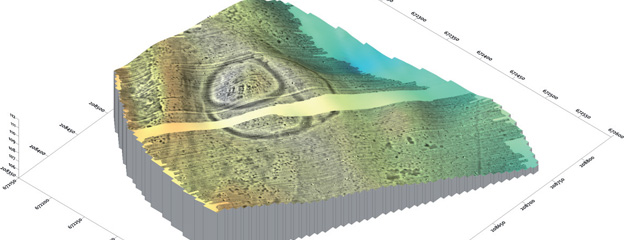

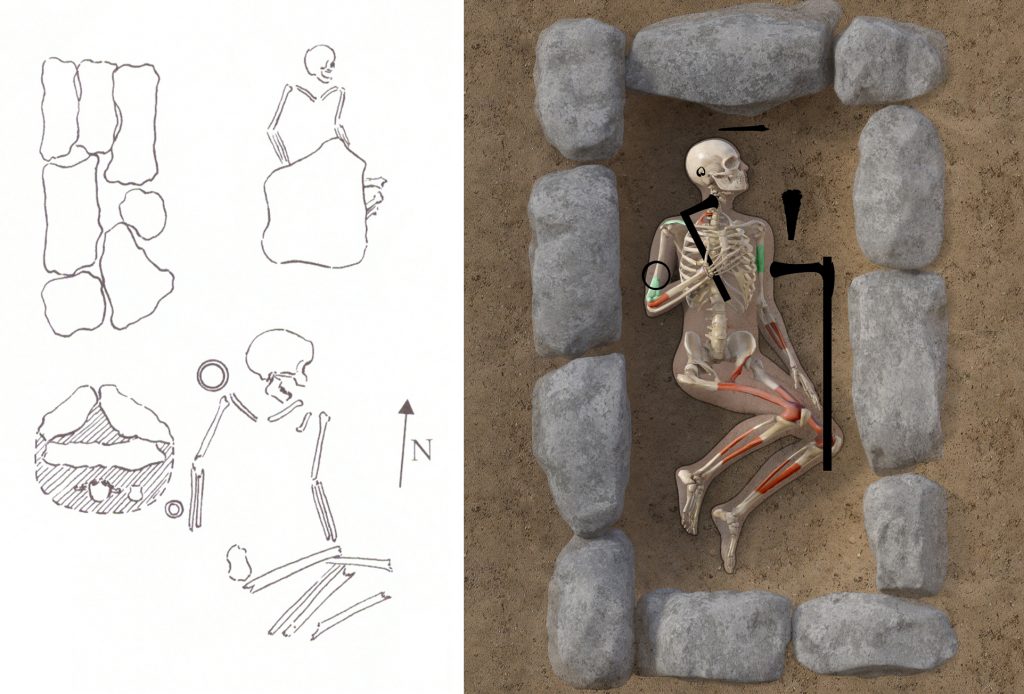

According to the description of the construction workers, the skeleton was found under large stone slabs, which, like bronze weapons and gold jewelery indicating high status, refers to the distinguished social position of a man aged 55-60 (Torma 1978). A similar burial covered with stone slabs is known from Dunaújváros; here and in other contemporaneous cemeteries men were often laid on their left side, with their legs raised, lying on their side in a sleeping pose-like position, or with their upper body lying on their back, their head turned and their feet turned sideways (Kulcsár–Kiss 2016). The stone packing could also be placed above and around the body, as shown in our three-dimensional reconstruction drawing. The remaining pieces of the skeleton are marked in brown, and the bones in bronze patina in contact with metal objects are marked in green.

Dunaújváros grave 185 (Vicze 2011, Pl. 14.3-4), reconstruction drawing of the chief’s grave in Balatonakali (graphics: Zsolt Réti)

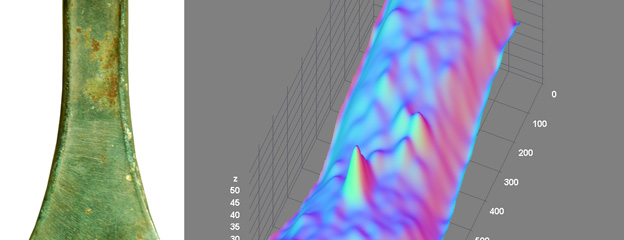

The position of the objects found in the burial was recorded by the archaeologist, Márta H. Kelemen, during her visit at the site. According to her description, the gold ring was found around the right side of the skull; a chisel above the skull, a special-shaped axe, while a flanged axe, a dagger, and a spiral bracelet were found at the left side of the skeleton. The location of the vessels found in the grave is unknown, but based on burials of the period they were most likely placed next to the head and feet. The organic (wood) handles of the axes or the dagger are only preserved by special conditions (e.g. under water or in frosty environment). Based on lucky cases, e.g. Ötzi’s 5,300-year-old tools and weapons preserved by the ice, and the few wooden remains known from the time of the Balatonakali burial in Hungary, as well as on the basis of metal-handled halberds and solid-handled daggers, we can imagine the original shape of these objects with handles.

The blade of the Balatonakali dagger (photo: Péter Hámori) and a solid-hilted dagger from Szentgál (Ilon 2015, Fig. 50)

It is known from the above mentioned metal handles and preserved wooden-handled objects that similar axes and halberds are generally provided with handles between 60 cm and 1 m in length (Rassmann–Schocknecht 1997; Needham 2015, Fig. 18); accordingly depicted in the reconstruction drawing of the tomb.

A metal-handled axe and halberds similar to the spacial bronze axe, found in the Balatonakali burial are from the Melz II hoard (Rassmann–Schoknecht 1997, Abb. 1); we can imagine the flanged axe from Balatonakali based on the wooden axe of Ötzi (© South Tyrol Museum of Archeology)

Reconstruction of the chief’s clothing

Few textile remains are known from Central European prehistory, since, as mentioned, organic materials such as fabrics made from plants (e.g. flax, hemp) and animal (wool) materials are only preserved under special conditions, such as water, ice or acid, or preserved by the corrosion of metal objects. Depictions from which clothing of the period can be deduced are also rare: these include Scandinavian rock carvings and Mediterranean wall paintings, or scenes depicted on contemporaneous ceramic pots or metal artefacts. Even rarer are pieces of roughly complete garments, such as ones that were preserved by the wooden coffins of the burials of elite persons from 1300 BC, discovered in Denmark: a female top and a cord skirt, or men ‘s woolen coats and hats (Bergerbrant 2007).

The hunting scene seen on the blade of a dagger, found in the shaft graves of Mycenae, shows the garment of the Bronze Age Greek warriors (Berger et al. 2013, Fig. 8).

We can form a picture of – mainly female – clothing and jewelry of the Bronze Age communities living in the Carpathian Basin on the basis of small anthropomorphic statuettes (Kiss 2017).

Middle Bronze Age statuette from the Lower Danube region, depicting bronze ornaments and embroidered textiles (V. Szabó 2015, III. 84)

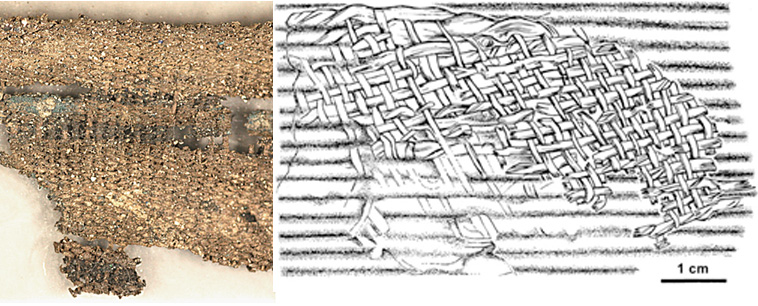

Bronze Age textiles made of plant materials are referred to from potsherds with impressions of twining technique of the surface, which were found at multi-layered settlements inhabited between 2000 and 1500 BC in eastern Hungary, or from fragment of linen cloth survived by corrosion of a bronze head ornament in eastern Austrian burial of the period (21-20th century BC; Grömer–Bender Jørgensen 2018). Some woolen textile remains are also known from the period, such as the Tursko site in the Czech Republic (18-17th century BC) preserved in the corrosion layer of a bracelet (Vykouková et al. 2007). The bones of elderly sheep found in animal bone material of the multi-layered settlements of Central Hungary, that were bred presumably not for their meat but for their wool, also indicate the importance of textiles of animal origin (Vretemark–Sten 2005). The latter wool textiles are a rarer find, presumably only available to a few, especially the elite of the era.

Striped linen from Franzhausen (Austria) Grave 110 and woolen fabric from Tursko-Těšina (Czech Republik) (Grömer–Bender Jørgensen 2018, Fig. 2; Vykouková et al. 2007)

We have seen that we have only indirect data referring to prehistoric clothing due to climatic and soil conditions that did not allow the textiles to survive in the territory of today’s Hungary. However, in the graves of the aforementioned Danish nobles buried in oak coffins, Bronze Age garments made of wool and leather were preserved in extraordinary integrity. The male burials excavated at Trindhøj included, for example, contained a woolen cap and a wrapped short tunic, cloak, gaiters and leather sandal (Bergerbrant 2007, Fig. 36).

Bronze Age man’s burial with clothes and weapons preserved in oak coffin from Trindhøj, Denmark (Iversen 2017, Fig. 3)

Leg gaiters were found next to the Copper Age Ötzi’s body. We only know of evidence for the wearing of trousers from a much later period, around the transition of the Late Bronze and the Early Iron Ages. Thus, we do not reconstruct the clothing of the chief from Balatonakali in trousers, but in a garment similar to the ones mentioned from the burials from Denmark, and with gaiters known from the Copper and Bronze Ages. Textiles could certainly have been supplemented with clothes made of leather and fur. Examples of the latter are Ötzi’s 5300 year-old fur coat made of bearskin, as well as the remains of a hat also decorated with bearskin, which was discovered from a female burial at Whitehorse Hill in Scotland between 1730 and 1600 (Jones 2017).

Reconstruction of a male clothing based on the findings of Scandinavian Bronze Age oak coffin graves and a female costume known from the findings of the burial excavated at Whitehorse Hill (Great Britain, National Museums Scotland)

In our reconstruction drawing, the chiefs’s flax or hemp cloth, gaiters and leather shoes are complemented by the wool hat and fur cape, which is a rarity status symbol in the era.

Possible reconstruction of the chief of Balatonakali (drawing by Dávid Ringeisen)

Viktória Kiss

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Judit Pásztókai-Szeőke for interpreting the prehistoric textile remains. The reconstruction of the discovery of the Balatonakali grave can be seen on our film entitled Bronze Age Mysteries (created by Real Pictures Production). We also recommend the BBC film Mystery of the Moor based on the study findings at Whitehorse Hill (Great Britain).

References:

Berger, D., Hunger, K., Bolliger-Schreyer, S., Grolimund, D.: New insights into Early Bronze Age damascene technique north of the Alps. The Antiquaries Journal 93 (2013) 1–29.

Bergerbrant, S.: Bronze Age Identities: Costume, Conflict and Contact in Northern Europe 1600-1300 BC. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 43. Stockholm 2007.

Grömer, K.–Bender Jørgensen, L.: Visuality – Movement – Performance. The costume of a rich woman from Franzhausen in Austria, c. 2000 BC. In: Manel Garda Sanchez, Margarita Gleba (eds.): Vetus Textrinum. Textiles in the Ancient World. Studies in honour of Carmen Alfaro Giner. Barcelona 2018, 211–224.

Ilon, G.: Veszprém megye bronz- és kora vaskora. LDM Online 2 (2018) 1–46.

Iversen, R.: Big-Men and Small Chiefs: The Creation of Bronze Age Societies. Open Archaeology 3 (2017) 361–375.

Jones, M.: Preserved in the Peat: An Extraordinary Bronze Age Burial on Whitehorse Hill, Dartmoor, and its Wider Context. Oxford 2017.

Kiss V.: Színek, fény, csillogás. Művészet és viselet a középső bronzkorban. In: Dani J., Kolozsi B., Nagy E. Gy., Priskin A.(szerk.): ΜΩΜΟΣ VIII. Őskoros Kutatók VIII. Összejövetelének konferenciakötete – Őskori műveszet – Művészet az őskorban. Debrecen 2017, 251–268.

Kulcsár G.–Kiss V.: Újra a balatonakali bronzkori sírról – The Bronze Age burial from Balatonakali – revisited. Tisicum 25 (2016) 75–82.

Needham, S.: A Hafted Halberd Excavated at Trecastell, Powys: from Undercurrent to Uptake. The Emergence and Contextualisation of Halberds in Wales and North-west Europe. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 81 (2015) 1–41.

Pásztókai-Szeőke J., Szathmári I., Kiss V., Kulcsár G.: Sző? Fon? Bronzkori textiltechnológia a Füzesabony-öregdombi tellen előkerült lenyomatok és eszközök alapján. In: Vicze M, T. Németh G, Kovács G. (szerk.): MΩMOΣ X. Őskori technikák, őskori technológiák.Őskoros Kutatók X. Összejövetele, Százhalombatta, 2017. április 6–8. Absztrakt füzet. Százhalombatta, 2017, 8.

Rassmann, K., Schoknecht, U.: Insignien der Macht – Die Stabdolche aus dem Depot von Melz II. In: Hänsel, B., Hänsel, A. (Hrsg.): Gaben an die Götter. Schätze der Bronzezeit Europas. Ausstellung der Freien Universität Berlin. Bestandskataloge, Band 4. Berlin 1997, 43–47.

Torma István: A balatonakali bronzkori sír – Das bronzezeitliche Grab in Balatonakali. Veszprém Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei 13 (1978) 15–24.

Vicze, M.: Bronze Age Cemetery at Dunaújváros-Duna-dűlő. Dissertationes Pannonicae IV(1). Budapest 2011.

Vykouková, J., Březinová, H., Fikrle, M. Frána, J., Králík, M., Lutovský, M., Samohýlová, A., Smejtek, L. Náramky z Turska-Těšiny. Několik pohledů na unikátní šperk únětické kultury – Bracelets from Tursko-Těšina: Several perspectives on unique Unětice culture jewellery. Archeologie ve Středních Čechách 11 (2007) 205–225.

Vretemark, M.–Sten, S.: Diet and animal husbandry during the Bronze Age. An analysis of animal bones from Százhalombatta-Földvár. Százhalombatta Arcaheological Expedition SAX – Report 2. Field Seasons 2002-2003. Százhalombatta 2005, 157–180.